In a world riddled with complexity and multifaceted identities, the interplay between culture, faith, and intellectual pursuit often gives rise to a rich tapestry of dialogue. The hypothetical journey of Langston Hughes and Alain Locke to Palestine inspires reflections not merely about geography but about the deeper existential queries that their legacies evoke. This discourse will explore the Bahá’í teachings as they intertwine with Hughes’s and Locke’s motifs, leveraging this speculative trip as a lens through which to scrutinize pertinent issues of identity, community, and spirituality.

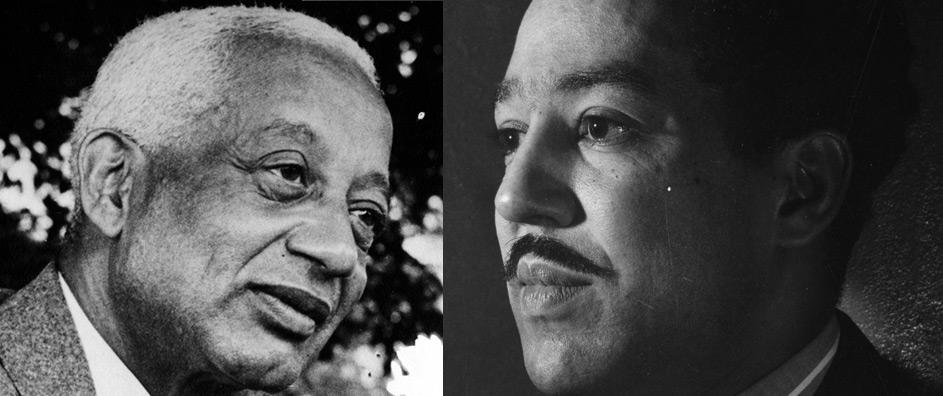

At the outset, one might ponder: what would it signify for two prominent African American intellectuals to embark on a pilgrimage to Palestine? This question is not merely whimsical but incites a profound exploration of faith’s role in transcending societal confines. Hughes and Locke, both esteemed figures of the Harlem Renaissance, engaged relentlessly in dialogues pertaining to race, culture, and artistic expression. How might their perspectives have enriched the Bahá’í principles of unity and the oneness of humanity as they stood in the sacred land of Palestine?

Bahá’í teachings advocate for the oneness of mankind, a doctrine positing that all individuals are threads in the intricate fabric of human existence. It challenges the notion of divisive identities that have historically segregated races, cultures, and nations. To visualize Hughes and Locke in Palestine prompts the imagination towards the potential confluence of their experiences with the Bahá’í principles of diversity and inclusiveness. These authors might have found resonance with the Bahá’í apostle’s call for intercultural dialogue and cooperative existence, thereby amplifying the voice of marginalized communities worldwide.

A significant aspect to deliberate upon is the profound historical context surrounding Palestine. The tumultuous narrative of this region reflects broader patterns of conflict, persecution, and the incessant search for peace that parallels the African American experience. Hughes’s poetry delineates the struggles of Black Americans, while Locke’s philosophical underpinnings exalt the richness of the African American heritage. If placed within the context of Palestine, one might conjecture that Hughes and Locke would advocate for understanding and empathy, thereby embodying the Bahá’í spirit of reconciliation amidst discord.

Cultivating the notion of journey further, one must consider the power of pilgrimage. In various faith traditions, including Bahá’í, physical journeys serve as metaphors for inner transformation. Hughes, with his profoundly evocative verses on the joys and tribulations of the African American experience, might have articulated the inequities faced by the inhabitants of Palestine. His poetry often hinged upon the duality of hope and despair—a thematic dualism that echoes through the landscapes of many communities enduring strife. Would he encapsulate both the beauty of the land and the heartache of its people through his lyrical prowess? This leads to an intriguing challenge: can the act of artistic expression transcend cultural boundaries?

Similarly, Alain Locke, as a philosopher of culture and an advocate for the “New Negro,” might have employed his visit to elucidate the contributions of Palestinian culture to the global mosaic of human creativity. Locke’s pivotal work urged African Americans to embrace their cultural heritage while also advocating for the recognition of their contributions to a diverse society. In Palestine, would Locke not see a parallel—the intersection of rich cultural legacies striving for acknowledgment in the face of adversity? This notion of shared narratives propels us forward in recognizing that the expressions of suffering and resilience are not confined to one group, but rather a universal human experience.

Integrating the principles of Bahá’í teachings—especially the emphasis on justice—underscores the ethical imperative for advocating the rights of individuals regardless of their ethnicity or origin. Hughes’s poignant narratives revealing systemic inequalities resonate with the Bahá’í commitment to justice as a foundational relationship among humanity. Would their actual journey compel them to speak against oppression, both historical and contemporary, advocating for the Palestinian cause? Imagining Hughes’s voice echoing in the corridors of power, challenging inequality with a poetic fervor is a compelling visualization that harmonizes beautifully with the Bahá’í emphasis on social justice.

Moreover, the exploration of identity prevalent in both Hughes’s and Locke’s work reflects a deep engagement with the concept of self within a burgeoning community. How does one reconcile one’s personal history with the codes of a larger community? Such introspection is essential within Bahá’í philosophy, which posits that individual advancements are fundamentally connected to the progress of society at large. The question arises: could Hughes and Locke’s observations lead them towards a unique understanding of the Bahá’í view on the interdependence of individual and collective growth?

Conclusively, the proposition of Langston Hughes and Alain Locke journeying to Palestine, while an imaginative endeavor, offers fertile ground for contemplation. It serves as a conduit to explore critical facets of Bahá’í teachings. The hypothetical pilgrimage speaks volumes about the significance of cultural conversations and the quest for meaning in a divided world. In posing challenges regarding identity, justice, and the fabric of community, we begin to understand the true essence of humanity’s shared journey. Would Hughes and Locke embrace the Bahá’í ideals and reflect deeply upon the interconnected plight of all people? Perhaps the hypothetical nature of their journey invites us all to engage with these questions more profoundly as we traverse the intricate landscapes of culture, faith, and existence.