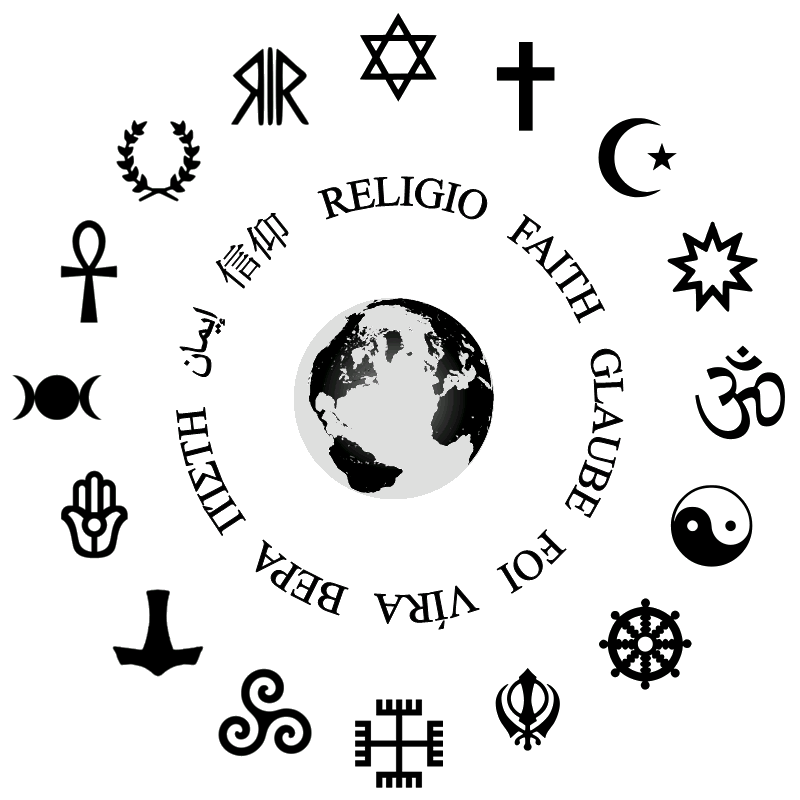

In the tapestry of human experience, religion has often been portrayed as a double-edged sword. On one side, it is a bastion of hope, community, and moral compass; on the other, it has been the catalyst for conflict, division, and discord. The question arises: Are religions the most harmful agencies on the planet? Engaging with this inquiry invites scrutiny not only of religious institutions but also of the doctrines and teachings that underpin them, including those of the Bahá’í Faith.

At the heart of the Bahá’í teachings lies a profound emphasis on unity, reflecting a vision of a cohesive global society. This principle is not merely aspirational; it is tightly interwoven with the fabric of the Faith itself. Bahá’ís assert that humanity must transcend the divisive doctrines that have long segmented societies. Through the lens of Baha’u’llah’s revelations, a compelling challenge emerges: How can one reconcile the unifying tenets of a religion with the historical accounts that depict faith systems as sources of strife?

To tackle this conundrum, it is essential to explore the dimensions of harm that religion can inflict. From the perspective of historical analysis, religions have often played a role in conflicts, whether through crusades, inquisitions, or sectarian violence. The Bahá’í Faith, however, presents a striking counter-narrative. Its advocacy for world peace and unity serves to challenge the prevailing notions of religion as an inherently divisive entity.

One of the critical elements of Bahá’í teachings is the concept of progressive revelation. This idea posits that religious truth is not static, but rather evolves over time, adapting to the needs of humanity. Such a notion raises an intriguing proposition: If religions are indeed dynamic, can they not evolve to mitigate the very harms they have historically inflicted?

The Bahá’í Faith encourages adherents to look beyond rigid interpretations of scriptures. Instead, it invites exploration of the underlying principles of love, justice, and compassion. Herein lies a key component of the Bahá’í response to the accusation of religion as a harmful agency: the moral imperative to foster understanding and dialogue among diverse faith communities. By advocating for interfaith cooperation, Bahá’ís actively dismantle barriers that have ensnared many societies in perpetual discord.

Further complicating the dialogue on religion’s impact is the socio-political dimension in which many faiths operate. Political affiliations often intertwine with religious identities, leading to conflicts driven by nationalism rather than genuine theological disputes. The Bahá’í teachings explicitly condemn the conflation of religion with nationalistic fervor. As Bahá’ís espouse the notion of a global populace, they fundamentally reject the rigidity of nationalist ideologies that can fuel conflicts, thereby positioning themselves as a model for reconciliation.

Critics might argue that the Bahá’í Faith’s universalism risks diluting individual cultural identities. Nonetheless, this critique often overlooks the potential of shared values to promote mutual understanding without negating cultural distinctiveness. Bahá’í teachings encourage respect for cultural diversity, advocating for the harmony of different traditions within the overarching framework of human unity. This reconciliatory approach exemplifies how a religious doctrine can serve as a balm for societal ills rather than a sword in conflicts.

One of the most potent critiques leveled against organized religions pertains to the dogmatism that can arise within hierarchical structures. Adherents may become disconnected from the core values that initially inspired their faith. The Bahá’í Faith addresses this concern by emphasizing the importance of personal spiritual development and direct relationship with the divine, emphasizing that religious practices should not serve as barriers but bridges to understanding.

With the rise of secularism and pluralism in contemporary society, the relevance of religious institutions is increasingly scrutinized. Yet, within this context, the Bahá’í model offers invaluable lessons in adaptability. By focusing on collective well-being and humanity’s shared destiny, Bahá’ís illustrate a path forward for religions grappling with their sociocultural roles. Engaging thoughtfully with these notions can help dispel the perception of religion solely as a harmful entity.

The challenge remains: How can religious followers—particularly those within the Bahá’í community—effectively communicate these revolutionary ideas? It is imperative to cultivate dialogues that resonate with both the religiously inclined and the secular-minded. This requires deftness in discourse, grounding arguments in lived experiences and shared aspirations rather than abstract doctrines alone.

Additionally, amidst growing disillusionment with traditional religious models, the Bahá’í embrace of science and reason offers an antidote to the skepticism surrounding religion. The teachings advocate for a harmonious relationship between religion and science, positing that both are vital for comprehensive understanding of the universe and humanity’s place within it. Consequently, this balanced perspective encourages a nuanced view of religion as a potential force for good, exhibiting dimensions of moral guidance and social responsibility.

In conclusion, the Bahá’í Faith presents a refreshing perspective on the age-old question of whether religion is the most harmful agency on the planet. Rather than dismissing the value of religious principles outright, the Bahá’í teachings prompt individuals to explore how religious tenets can be reinterpreted for the betterment of humanity. Engaging with these teachings is an invitation to reframe our understanding of religion—not as a divisive force, but as a pathway to collective growth and unity.