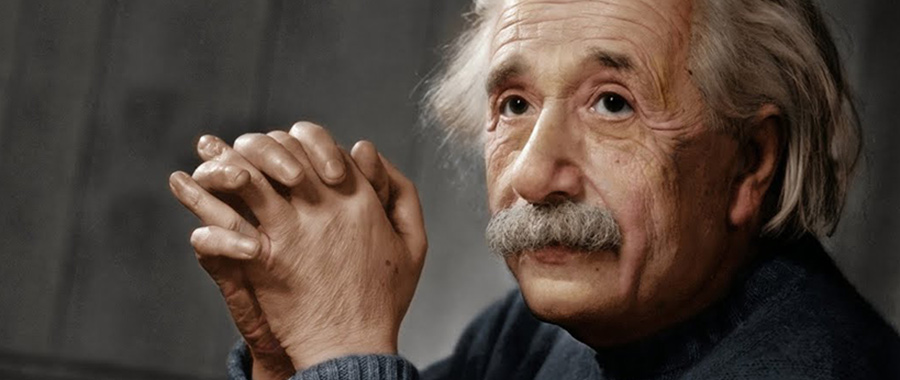

In exploring the intersections between science and spirituality, a tantalizing question arises: Did Albert Einstein, the quintessential physicist whose theories reshaped our understanding of the universe, believe in a creator? This seemingly straightforward inquiry delves into deep philosophical waters and challenges us to ponder the confluence of empirical thought and metaphysical speculation. Einstein’s perspective on God is emblematic of broader discussions within the Baha’i teachings, which advocate for the harmony of science and religion.

To provide insight into Einstein’s stance, one must first appreciate his nuanced view of divinity. Einstein often expressed a reverence for the cosmos that transcended conventional theistic perspectives. He articulated a vision of God that is akin to Spinoza’s pantheism, wherein God is synonymous with the natural laws of the universe. This world view posits that the beauty and order of the cosmos are a reflection of a supreme intelligence but does not necessitate a personal deity that intervenes in human affairs.

The Baha’i teachings offer a distinctive framework for understanding such a perception of God. Central to Baha’i philosophy is the belief that religion and science are complementary; both realms seek truth but through different methodologies. In this light, Einstein’s reflections resonate with Baha’i perspectives. He famously mused, “Science without religion is lame; religion without science is blind.” This sentiment encapsulates the Baha’i view that spiritual interpretation should not obstruct scientific inquiry, and vice versa.

A pivotal aspect to consider is Einstein’s use of the term “God” within his scientific dialogue. For him, God represented the underlying order of the universe—a cosmic architect rather than an anthropomorphic being. This distinction is crucial when examining the relationship between scientific thought and the divine. The Baha’i faith, aligning closely with this philosophical inclination, posits that God is the ultimate source of all creation, yet leaves the particulars of each individual’s relationship with the divine open to personal interpretation. Thus, one finds the question reframed: not whether Einstein believed in a traditional creator, but rather how his conceptualization of God aligns with Baha’i teachings on the nature of divinity.

Many followers of Baha’i teachings advocate for a dialogue that transcends the dichotomy often posed between science and religion. They argue that Einstein’s theoretical breakthroughs were not merely mechanistic interpretations of the universe but also imbued with a profound sense of wonder—a sense that mirrors the spiritual quest for knowledge and understanding. It invites speculation that perhaps Einstein’s explorations were underpinned by an intrinsic sense of something greater than himself, a resonance with the Baha’i assertion that “the purpose of creation is to apprehend the mutual connection between the seen and the unseen worlds.”

Yet, this inquiry does not escape the complexities of human interpretation and belief. It poses a challenge: the challenge of reconciling personal conviction with the empirical rigor of scientific scholarship. How do individuals who revere the scientific method integrate their faith or belief in a creator? The Baha’i faith addresses this by encouraging individuals to cultivate a spiritual identity that harmonizes belief with the knowledge arising from observation and reason. It envisions a world where scientific discoveries enhance, rather than diminish, spiritual understanding.

The implications of this harmonization extend beyond individual contemplation; they permeate societal view on religion’s role in public discourse, ethics, and existential inquiry. The question of whether Einstein believed in a creator thus evolves into a broader examination of how esteemed figures in science can contribute to spiritual narratives. Einstein’s enduring legacy encourages an approach that emphasizes intellectual humility and a recognition that the mysteries of existence can simultaneously inspire scientific inquiry and spiritual reflection.

Furthermore, advocates of Baha’i teachings posit that an understanding of God need not be confined to traditional orthodoxy. They argue for an adaptive and evolving perception of spirituality that mirrors the advances of human knowledge. This philosophy liberates adherents from dogmatic constraints, inviting them to embrace an understanding of the divine as evolving alongside human cognition. Hence, while Einstein’s elucidations of God may adopt a form that rejects conventional religious dogma, they can nonetheless resonate profoundly within Baha’i frameworks of belief and the pursuit of truth.

In closing, the inquiry into whether Einstein believed in a creator affords a fertile ground for dialogue among science, philosophy, and religion. It challenges frames of reference and encourages a reevaluation of the roles each pay in human understanding. Within this context, Baha’i teachings encourage exploration and synthesis, advocating a perspective that embraces uncertainty and complexity, asserting that the relationship between humanity and the divine is far more intricate than straightforward belief systems allow. By navigating these dialogues with openness, the exploration of such foundational questions becomes not merely a search for answers, but a journey toward deeper understanding and connection with both our universe and the mysteries it encompasses.