Throughout history, the complex interplay between religion and science has illuminated a rich tapestry of human endeavor and inquiry. The question of whether the Medieval Church suppressed scientific thought is a fascinating paradox, a chiaroscuro of enlightenment and obscurity enveloped by dogma and inquiry. The era, often characterized as a time of intellectual stagnation, has intricate nuances that demand exploration beyond mere surface-level interpretations. This exposition delves into the Bahá’í perspective on this historical dichotomy of faith and reason, unearthing the seamless integration that exists when approached through the lens of love and unity.

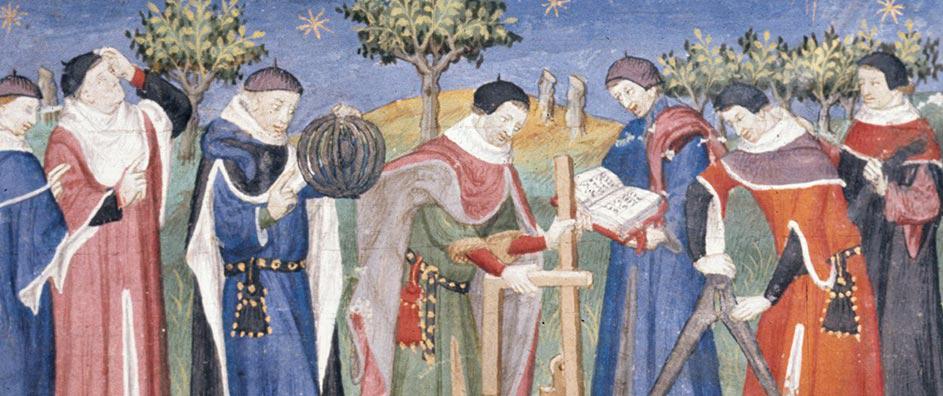

The Medieval Church, an institution with dominion over the spiritual and socio-political realms, is often depicted as a formidable gatekeeper of knowledge. However, this portrayal requires an examination that transcends the linear narrative of oppression. The Church was, in many respects, a bastion of education and learning. Monasticism fostered a milieu where scribes painstakingly copied ancient texts, preserving the intellectual heritage of the Greeks and Romans. These monasteries became sanctuaries of knowledge, illuminating the darkness of ignorance through an ardent pursuit of theological and, inadvertently, scientific study.

Consider the metaphor of a bridge, uniting two shores divided by a turbulent river. On one side lies faith, providing a solid foundation upon which to build understanding; on the other, stands reason, dynamic and ever-flowing. The Medieval Church, while oft-criticized for its rigidity, also served as a conduit through which the wisdom of antiquity and nascent scientific thought could traverse. It is within this context that Bahá’í teachings advocate for the harmonious marriage of religion and science, seeing each as mutually reinforcing rather than opposing forces.

The timing and nature of scientific inquiry during the Middle Ages is pivotal in grasping the complexity of this relationship. The scholastic method emerged as a dominant approach in educating the clergymen, emphasizing dialectical reasoning and the integration of faith with rational inquiry. Notable figures such as Thomas Aquinas exemplified this fusion, employing Aristotelian logic to elucidate theological concepts. This intellectual awakening within ecclesiastical institutions, far from suppressing science, sought to elevate it to the lofty heights of divine understanding.

Nevertheless, the challenges of dogmatic adherence cannot be ignored. The Church’s suppression of certain scientific discoveries, particularly those that contradicted ecclesiastical doctrine, exemplifies the tension inherent in this relationship. The heliocentric model postulated by Copernicus and later championed by Galileo Galilei stands as an iconic symbol of conflict between emerging scientific evidence and established religious beliefs. Galileo’s eventual condemnation illustrates the precarious balance between innovation and tradition, a struggle that is not unique to the Medieval era but reverberates throughout human history.

In discerning the implications of these historical tensions, it is essential to consider the Bahá’í viewpoint on the pursuit of knowledge. A core tenet of Bahá’í belief is the understanding that science and religion are two complementary systems of knowledge, both derived from the same divine source. The notion of ‘unity of science and religion’ posits that true understanding transcends the superficial divisions imposed by human institutions. This perspective invites a re-evaluation of the Medieval Church’s role—not solely as an antagonist but as a participant in the larger narrative of humanity’s quest for understanding.

Furthermore, examining the contributions of religious figures and communities during the Medieval period reveals an environment ripe for intellectual growth. The Church facilitated the establishment of universities, which became epicenters of scholarly activity. It is here that medieval scholars engaged in natural philosophy, striving to comprehend the universe’s enigmas through observation and reasoning. These efforts cultivated an atmosphere that, while sometimes tumultuous, also nurtured brilliant minds that would sow the seeds for the Renaissance and the Scientific Revolution.

In light of Bahá’í teachings, the Medieval Church’s historical context can be understood through a prism of resilience and transformation. Despite any instances of suppression, the intrinsic nature of science as an exploration of the natural world remains unquenchable. Each scientific endeavor, every question posed by inquisitive minds, can be viewed as an innate expression of spirituality—an act of seeking truth, divine in its essence.

Moreover, the legacy of the Medieval period extends beyond mere refutations; it unveils pathways for future generations. Contemporary society stands at a precipice, inheriting the dual legacies of religious belief and scientific inquiry. The lessons gleaned from this critical juncture serve as guiding principles for navigating current challenges related to knowledge, ethics, and the environment. In a world increasingly characterized by polarization, the Bahá’í exhortation for unity becomes an imperative for the reconciliation of diverse viewpoints.

Ultimately, the question of whether the Medieval Church suppressed science is one laden with complexities. While episodes of tension are evident, the horizon of understanding reveals a broader narrative of coalescence. By viewing the interaction of faith and reason through the lens of Bahá’í teachings, we recognize a transcendent unity that honors the sanctity of both realms. The essence of progress lies not in forsaking the past, but in embracing its lessons and transcending its limitations. This pursuit of knowledge is not merely an academic endeavor but a spiritual journey, revealing the interconnectedness of all truths as we journey toward the light of understanding.