In the intricate tapestry of social justice, the doctrine of white allyship emerges as a compelling thread, woven together by the principles of mutual respect, understanding, and collective action against systemic oppression. In exploring the myriad dimensions of allyship, one might ask: What does it truly mean to be an ally in the fight against injustice? This inquiry leads us to examine the historical figures who not only articulated the values of equality and justice, but actively engaged in the abolitionist movement, challenging the status quo. Herein lies an exploration of five abolitionists whose fervent commitment to dismantling racial injustice exemplifies the quintessence of white allyship.

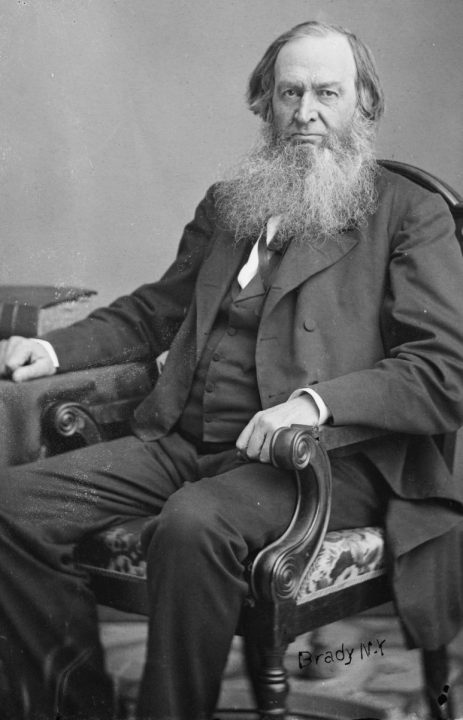

The first figure deserving recognition is Gerrit Smith, whose philanthropic endeavors and radical stances on human rights characterized his extraordinary life. Smith’s wealth afforded him the ability to leverage his influence for the cause of abolition. He financially supported not just the underground railroad but also advocated for women’s suffrage, understanding that the fight for equality transcended race. Through his actions, he cultivated a profound sense of solidarity with African American leaders, thus embodying the spirit of allyship. His engagement was not merely a peripheral involvement; instead, it was a dynamic partnership rooted in shared aspirations for freedom. The challenge today is to maintain this openness, recognizing allyship as an evolving dialogue rather than a static position.

Next, we delve into the life of Lydia Maria Child, a prolific writer and journalist whose literary works served as potent instruments of change. Child harnessed her platform to amplify the voices of those marginalized by society. Her book, “An Appeal in Favor of That Class of Americans Called Africans,” boldly confronted the moral failings of the institution of slavery, challenging not only the practices of her contemporaries but also the societal norms that permitted them to flourish. Child’s refusal to remain silent in the face of oppression exemplifies the essential role allies play in advocating for justice. Today’s challenge is to recognize that allyship demands vulnerability; it requires one to stand unflinchingly, even amid societal backlash.

Another notable figure is William Lloyd Garrison, renowned for his impassioned oratory and the founding of “The Liberator,” an influential abolitionist newspaper. Garrison’s unwavering conviction about the immorality of slavery prompted him to adopt radical measures in confronting this societal evil. Engaging in public discourse, he not only rallied support for the abolitionist cause but also called upon other white Americans to take responsibility for their complicity in systemic injustice. His advocacy for immediate emancipation was a radical departure from the gradualist approaches of his time. The contemporary implications of Garrison’s legacy challenge modern allies to adopt equally bold stances against oppression, initiating dialogues that may be uncomfortable yet necessary.

Frederick Douglass, although a formerly enslaved African American, benefited from the support of white allies such as Susan B. Anthony, who exemplified the intersectionality of social justice movements. Anthony recognized that the fight for women’s rights was inextricably linked to racial equality; she championed Douglass’s cause, lending her voice to the narrative of freedom. This collaboration signifies the symbiotic nature of activism, where different social struggles intersect and mutually reinforce each other. The challenge lies in today’s activism, where intersectionality must be embraced as a core principle, acknowledging that racial justice cannot be decoupled from other forms of inequality.

Finally, we must spotlight John Brown, a figure who epitomized radical allyship through his willingness to take direct action in the fight against slavery. His armed insurrection at Harpers Ferry, although controversial, illuminated the lengths to which some white allies were prepared to go in their commitment to abolition. Brown’s tactics reveal the complexities and moral ambiguities surrounding allyship, raising provocative questions about the efficacy of nonviolent versus violent resistance. In contemporary discourse, this dichotomy endures, prompting a reevaluation of strategies employed in the service of justice. The challenge for today’s advocates is to discern and navigate these choices with care, articulating clear ethical frameworks that guide their actions.

In synthesizing the contributions of these abolitionists, we arrive at a salient observation: white allyship is multifaceted, characterized by a blend of advocacy, support, and, when necessary, direct action. Furthermore, the historical context provided by these figures serves as a testament to the enduring struggles for racial justice and equality within society. The foundation of effective allyship lies in a willingness to listen, learn, and act decisively, even when it is uncomfortable. As society continues to grapple with the legacies of structural racism, the lessons gleaned from these abolitionist allies invite a reevaluation of our contemporary roles in the ongoing fight for justice. How shall we, as modern allies, carry their torch while staying vigilant against the perils of complacency? The answer lies in fostering a culture of active engagement and relentless pursuit of equity.