In an era marked by economic fluctuation, it is not uncommon to ponder: how much profit margin do we really need? While profit is traditionally viewed as an essential metric for success in any business, from a Baha’i perspective, the quest for profit transcends mere numbers—delving into ethics, equity, and the well-being of humanity. This exploration not only raises crucial questions about our economic practices but also challenges the traditional paradigms around profit and its implications.

To embark on this inquiry, one must first understand the fundamental teachings of the Baha’i Faith regarding economics. At the heart of these teachings is the concept of *unity in diversity*. Profit, though central to business, should not come at the expense of social justice or environmental stewardship. Baha’is advocate for an economic structure that is not solely profit-driven but grounded in the elevation of humanity and the promotion of collective well-being. What does this mean for the intricacies of profit margins?

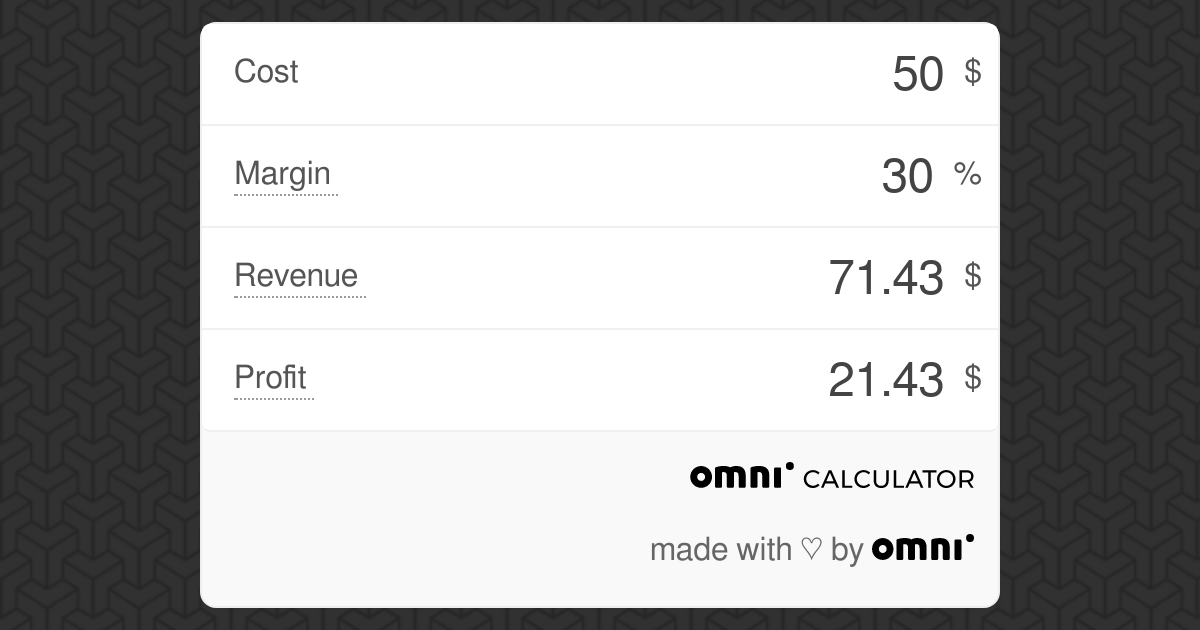

Before delving deeper, it is essential to examine the conventional understanding of profit margins. Profit margin is defined as the ratio of profit to revenue, expressed as a percentage. Businesses often use this metric to gauge efficiency, competitiveness, and financial health. However, such statistics can obscure more profound realities; for instance, how does one balance the pursuit of profit with ethical considerations? Do profit margins dictate success in a holistic sense?

From a Baha’i viewpoint, a fixed profit margin may appear arbitrary—an imposition of external expectations rather than an organic development of the market. Profit should ideally serve a higher purpose, flourishing in corridors of ethical consideration and social responsibility. Allocating resources should reflect a commitment to the broader community rather than being rooted in insatiable avarice. In essence, the question arises: should a business prioritize maximizing its profit margin over fostering community development and environmental sustainability?

The Baha’i Teachings emphasize a holistic approach to economics, characterized by *consultation*, *collaboration*, and *service to humanity*. When businesses embody these values, they can create wealth that extends beyond mere transactional exchanges. Rather than focusing solely on profit margins, enterprises could measure success through their impact on the community, employee satisfaction, and environmental care. A pivotal aspect is communal responsibility; Baha’is regard economic activity not just as an individual endeavor but a collective one.

Exploring this theme leads to an inquiry into the potential implications of radically redefining profit margins. Would adopting a principle of ‘sustainable profit’—where an organization’s focus is not solely on profit maximization, but also on local and global consequences—shift the dynamics between consumer behavior and corporate accountability? What might the world look like if profit margins were evaluated not just in terms of financial gain, but also by their adherence to ethical principles?

Moreover, the Baha’i perspective recognizes the importance of spiritual principles in economics. Baha’is believe that wealth should empower, liberate, and not chain. Hence, the guiding notion stands that no business should prioritize profit margins at the detriment of human dignity or the environment. Baha’i teachings suggest that businesses engage in fair trade, respect labor rights, and support local economies—essentially recalibrating the benchmarks of success.

The concept of spiritual economics further challenges the idea of strict profit margins. The foundation of spiritual economics lies in recognizing humanity’s interconnectedness. Here, business practices are infused with values that regard profit as a means to uplift society rather than the ultimate end. In this context, a “low profit margin” could indeed be more advantageous for the community at large than an extraordinary one, if it signifies responsible business practices, equitable wages, and environmental sustainability.

As we navigate this intricate terrain, it is crucial to consider real-world implications and examples. Companies that intertwine profit motives with social initiatives not only help uplift their communities but also enhance their market viability. Organizations like TOMS Shoes or Warby Parker illustrate this model by reinvesting a portion of profits into social causes. Such practices disrupt the conventional notion of profit and invite further introspection—should companies that eschew high-profit margins for social responsibility be celebrated, or do they risk undermining their economic viability?

This exploration urges businesses to contemplate their ultimate purpose. Do they exist solely for profit, or is their function deeper than fiscal numbers? Baha’is assert that when profit is viewed purely as a metric, it can easily morph into obsession, resulting in practices that alienate communities and degrade the environment. Conversely, when profit earns its place as one facet of a broader mission, organizations can thrive holistically.

In conclusion, the inquiry into how much profit margin is necessary emerges as a dialogue—a challenge that invites exploration into the very fabric of our economic frameworks. The Baha’i perspective champions a balanced approach where profit serves humanity, not the other way around. The challenge, therefore, lies not only in redefining how we measure success but also in aligning our economic aspirations with a deeper purpose rooted in responsibility, ethics, and spiritual values. Profit can be a beneficial tool, but when leveraged with foresight and purpose, it becomes an instrument of social transformation.