In the rich tapestry of Baha’i teachings, one encounters a profound exploration of action and its correlation with training. The delineation between training and doing extends beyond mere semantics; it embodies a dynamic interplay that can profoundly influence an individual’s spiritual and practical pursuits. This article aims to elucidate the distinctions while fostering a deeper understanding of how one might navigate the waters of training and action within the framework of Baha’i principles.

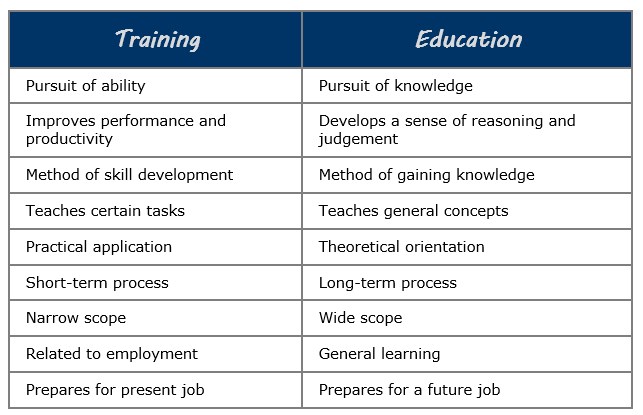

At the onset of this exploration, it is vital to establish definitions that resonate within the Baha’i context. Training can be understood as the systematic process of acquiring knowledge, skills, and competencies essential for effective functioning within various spheres of life. This encompasses formal education, workshops, and mentorship programs tailored to foster personal and professional growth. It is an initiatory phase, one that lays the groundwork for future actions.

Contrastingly, doing emerges as the tangible manifestation of one’s acquired training. It refers to the application of skills and knowledge through action, where the theoretical intertwines with the practical. In the Baha’i view, advancing society necessitates not merely knowledge but a commitment to implement that knowledge in actionable ways, thereby ensuring the teachings of Baha’u’llah are woven into the fabric of everyday life.

To further explore the dichotomy between training and doing, it is instrumental to consider the Baha’i teachings on education. The Baha’i Faith emphasizes the transformative power of education, not merely as a vehicle for personal advancement but as a means to cultivate virtues and contribute to the upliftment of humanity. Yet, education alone is insufficient; it serves as the precursor to action. The teachings articulate that “The best way to serve humanity is through the application of knowledge.” This maxim encapsulates the essence of bridging the gap between understanding and practice.

Exploring various types of training can yield insights into how one can effectively transition to action. Among these are spiritual training, vocational training, and social training. Each type serves a distinct purpose yet collectively contributes to the holistic development of the individual.

Spiritual training involves the cultivation of virtues, ethical understanding, and a sense of interconnectedness with humanity. Herein lies an emphasis on prayer, meditation, and participation in community life. Engaging in spiritual training prepares an individual to act with compassion and wisdom, virtues that are essential in a world rife with challenges. The teachings urge followers to be both the embodiment and the implementer of spiritual principles.

Vocational training, on the other hand, equips individuals with specific skills necessary for their professional endeavors. This training is crucial in enabling individuals to contribute positively to society and to support their communities financially and socially. Yet, the transition from training to doing necessitates that individuals understand their work as a service to humanity rather than merely a source of income. The distinction becomes significant when one views their vocation as a platform for implementing Baha’i principles in everyday interactions and decision-making processes.

Social training emphasizes community engagement and social responsibility. This form of training mandates experiential learning through participation in community service and collaborative projects. Baha’is are encouraged to foster collective action where knowledge gained through training is translated into initiatives that address societal needs. Here, doing becomes a collective endeavor, where varied skills and insights converge toward achieving common goals, illustrating the profound interconnectedness emphasized in Baha’i teachings.

Moreover, it is imperative to consider the impediments that may arise in the journey from training to doing. Over-reliance on theoretical knowledge, fear of failure, and complacency can hinder individuals from translating their training into actionable pursuits. The Baha’i teachings advocate for a proactive approach, urging individuals to embrace challenges as opportunities for growth. Each failure or setback serves as a learning moment, refining one’s approach to action. This philosophy of embracing resilience fosters a culture of perseverance that is crucial for navigating the complexities of real-world engagement.

Another significant aspect of this dialogue is the concept of ‘action without attachment.’ Baha’i writings articulate the importance of selfless service, where actions are undertaken devoid of personal gain or recognition. This intrinsic motivation reinforces the sanctity of action, encouraging individuals to contribute to the greater good and eschew the trappings of ego. The understanding that true progress leads to spiritual elevation reinforces the belief that doing is, in itself, a manifestation of training.

In conclusion, the profound differentiation between training and doing within the Baha’i framework invites individuals to rethink their approach to personal and community development. While training provides the necessary foundation of knowledge and skill, the act of doing is paramount in materializing those principles into reality. By recognizing the importance of this relationship, Baha’is can better navigate their responsibilities toward individual and collective progress. Such an understanding not only enhances personal growth but also facilitates the implementation of Baha’i teachings, contributing to a more harmonious and just society.